In this essay, I will first provide an exegesis of Mill’s harm principle then argue in favor of it by showing how existing laws that compel people to use certain speech violate this principle and infringe on rights and liberties that are essential to optimizing the utility of persons.

Mill argues that government intervention is only permissible over persons to prevent direct or indirect harm to others. Any other intervention will infringe on the utility of the individual. Mill argues that utilitarianism is the “ultimate appeal on all ethical questions” and the utility of people is maximized when they act and think as they want without coercion because it is in our nature as humans to act and think independently (Mill 1859, 14). This principle that justifies governmental intervention is called Mill’s harm principle.

Several terms within Mill’s description of permissible government intervention necessitate elaboration and definition. By Mill’s standard, harm can be understood as legal and tacit right violations. Interests should be understood as goods of life that make the beholder’s life better. By contrast, rights can be understood as the vital interests that society believes ought to be protected to maximize good for all people. Rights are distinct from interests in that rights are protected explicitly or implicitly by law and ought to be guaranteed to all citizens, whereas interests are not protected by law.

I will first elaborate on what goods should be perceived as solely interests then elaborate on what goods should be perceived as vital interests that ought to be considered rights in-order to make the distinction between interests and rights clearer. A person may have an interest in being accepted, but this interest cannot be viewed as a right because no government can intervene to guarantee this right without reducing the utility of individual persons. If the government intervened to protect the interest in being socially accepted sally, the government would have to coerce Joe and Juan into thinking or acting against their will to accept Sally, which would reduce the personal utility of the Joe and Juan because they were coerced. By contrast, people have an interest in free-association. The government should intervene to protect this interest. When people freely associate, they are acting out of their own volition and without coercion, which Mill argues is closer to human nature. Therefore, the interest in free-association should be considered a right because it maximizes the utility of individual persons.

Interests may also align with or evolve into rights. An example of an interest that is not a right is the interest in physical well-being. An example of an interest that should be considered a right is the right to not be physically harmed by others. The interest to enhance or retain physical well-being is self-regarding and, thus, an interest, whereas the interest to not be injured by other people is other regarding, and, thus, a right. For example, a person may desire to cut themselves, or cut other people. If the person cuts themselves, their actions of self-harm are self-regarding, so a protection against self-harm is considered an interest. Whereas, if some person cuts others, their actions are harmful to others and other-regarding, so a protection against this harm is considered a right. Mill argues that the government should only intervene in the latter because it is other-regarding and other-regarding actions can be considered harmful. This distinction between other-regarding and self-regarding can help to understand interests and rights as distinct ideas.

Mill argues that rights can be broken down into legal and tacit rights. Legal rights are those stated by law and tacit rights are duties that reasonable people believe we have to each other. A legal right is one which says a father shall not physically harm his children. An example of tacit right is a father’s duty to not physically harm his children while they are dependent on him for their well-being. It is implicitly understood that a father should care for his children because they are dependent on him. If the children’s personal utility is reduced due to physical harm, then government intervention is justified to maintain the health of the dependent children. This tacit expectation may not be explicitly written in law, though the public believes this is parental duty is valid.

Harm must be understood as the direct or indirect infringement on legal or tacit rights. Harmful infringements on rights are those that decrease the utility of the individual or reduce the ability of the individual to maximize their utility. Examples of harm are physical injury, coercion, right-infringing financial loss such as stealing, and inaction instead of action that could prevent harm to someone else. I will refer to the previous example of cutting yourself and others to elucidate the meanings of direct and indirect harm. A person that cuts another person causes direct harm to that person because that person has a right to not be physically injured by others. A person that cuts themselves may not be causing physical injury to anyone directly, but this self-harm could be considered harmful to others if, say, the self-harming person was a father of children that depended on him for their health and well-being and the harm inflicted on himself led to a deprivation of well-being for his children.

Harm does not include infringements of interests. To Mill, infringements of interests that are not considered rights are called offense. When a person is offended or displeased with the actions or behaviors of another, the offended person can act in ways to alleviate their suffering caused by displeasure or discomfort with avoidance of the conflicting person; with negative judgment either expressed or felt, and any other coping mechanisms that don’t harm the conflicting person. The government has no jurisdiction over these social conflicts that don’t constitute harm because they are self-regarding in nature.

The liberties that Mill believes are protected by this harm principle can be broken into three categories. One, the inward domain of consciousness, which states that the freedom to think, hold opinions and express one’s thoughts should be protected from control by outside forces. Two, persons should be able to plan their life no matter how perverse they may be, without obstruction, so long as they do not harm persons. Lastly, people should be able to unite and coalesce as they please without bringing any harm to people (Mill, 15).

To refute the objection “whatever affects himself may affect others through himself,” Mill offers recognition that actions may be offensive to the interests of groups or ascendant people, but so long as the actions of one don’t infringe upon the rights of others, the only reprobation an offensive person may receive legally is of the moral kind (Mill, 15). Objectionable behavior, dispositions or livelihoods may offend society’s interests by inviting others to follow-suit in their loathsome behavior, thus causing injury to society, or those affiliated with the loathsome person, but so long as this person does not hold a duty to the members of society to protect their legal and tacit rights, such as a police officer on duty, then the abhorrent person cannot lawfully be held accountable. A person with no “definite duty incumbent on him to the public” who chooses bad behavior is acting within the bounds of liberty that is protected under the harm principle since their behavior is solely self-regarding (Mill, 75). When the government intervenes to correct this disliked behavior, the majority is at risk of tyrannizing the minority and harming the utility of the individual. By Mill’s harm principle, individuals have the liberty to infringe upon the interests of society so long as the rights of society and its members are not infringed upon.

In cases where a person acts within their bounds of liberty, but nonetheless injures the interests of society, society is blameworthy for not educating or supporting the person in their development so that they contribute more positively to society. Society has major influence on the development of people, so if people offend society, society is partly responsible for not teaching or indoctrinating the youth to suit their liking. This will become relevant when I apply Mill’s harm principle to speech acts.

Mill argues that the strongest argument against the interference of society in personal and self-regarding matters is the argument that the thinkers or groups of society with power are often wrong in their idea morality and ideal personal conduct. Ideals of personal conduct are always construed with biases against certain modes of being. The interest of one person is not guaranteed to be the interest of other people. If one person imposes their personal interests on others, this is a utility reducing act because the imposed person is being coerced into adopting a foreign interest. Mill uses an example of religion which is guaranteed to hold doctrines of sinfulness that outlaw immoral and impious behaviors that followers of the religion follow with unwavering diligence (Mill, 78). To the followers, the doctrines of impiety are rational, true, and absolute, but it’s often the case that non-followers won’t accept these doctrines as rational or moral. This same contradiction of moral reasoning and ideology is guaranteed at some level for all people and all ideologies. There is no guaranteed ubiquitous morality among people. Therefore, any interference by a governing body on the individual with matters that only concern himself infringes on his liberty and thus decreases his utility, which, in Mill’s opinion constitutes harm.

Now, I’m going to argue in favor of Mill’s harm principle in cases of speech acts. I will show that legislation compelling people to use preferred pronouns violates the harm principle because a failure to use preferred pronouns does not constitute harm. Specifically, people do not have the right to be called what they want, and the government has no jurisdiction over the language people refer to each other with.

First, I think it necessary to elaborate on statutes passed in both the United States and Canada that enforce the use of preferred pronouns explicitly. Canada’s bill C-16, an amendment to the Human Rights act and Criminal Code, states that gender identity and gender expression are prohibited grounds of discrimination and if such alleged discrimination is motivated by bias, prejudice or hate then the court will consider this as unlawful discrimination. In New York the New York City Commission on Human Rights requires professionals and landlords to use a person’s preferred pronoun regardless of the individual’s sex assigned at birth, or face charges of up to $150,000.

I will refer to these statutes after I first argue that Mill’s harm principle is valid and applicable to speech acts.

Freedom of thought and feeling, opinion and sentiment, and the freedom to express these are the essential liberties of consciousness that should be guaranteed by any society to prevent the tyranny of the majority on the minority (Mill, 15-16). Infringement on the freedom of consciousness, if unrestricted by the society, can directly coerce people into thinking, speaking, and acting in ways that satisfy the dominant culture at-large, regardless of what counter-argument or objections they have of the dominant ideologies. The pressure to say and think in alignment with policy makers to preserve one’s self-governance and avoid imprisonment or financial burden is likely to outdo the pressure to be honest with one’s own personal beliefs about an ideal of the conscious type. Most people will not choose to have the integrity to stand up for one’s ideals and risk injury to their freedom of the physical type. Integrity and honesty are not tantamount for most people to the underlying drive for self-preservation. Most people will concede and cease to think and express themselves honestly to avoid incrimination and loss of status. In such a case where the freedom to speak and use language is compelled or restricted, the individual loses autonomy in his thought determination and loses the ability to express his thoughts or opinions. In this case, he is harmed since he is coerced into acting in accordance with other ideals and acting differently than he would if he wasn’t influenced, which should be considered a reduction in utility since autonomy of thought and expression are the foundation for personal utility.

The most common argument seen from the proponents of these laws is that these compelled speech laws provide legal recourse for trans* people who face discrimination in the workplace and school. These proponents argue that speech can be harmful if the speech prejudicially affects the status of the people targeted by the degrading language. This position has been argued by Noah Lewis in the Washington Post who asserts that enforcing the use of language is “about being able to work and attend school safely, free from discrimination” for trans* people (Lewis, 2016). Noah believes that repeated pronoun misnomers constitute discrimination and “convey a more insidious message: transgender people are not welcome at their schools” and in the workplace alike (Lewis, 2016).

At the surface level there seems to be a competition between the right to free speech and the right to not be harmed by others. Though, with deeper inspection and by clarifying what should be considered a right and what should be considered an interest, it can be shown that pronouns aren’t directly responsible for harm caused by discrimination and likely only affect trans* people by offense.

The feelings of discrimination felt by trans* people are, first, motivated by feelings, which aren’t protected by any of Mill’s description of rights. No rights as outlined by Mill lawfully allow for government intervention to prevent the infringement of interests related to feelings of acceptance or recognition. Mill clearly states that society has the legal ability to remonstrate, express disapproval, or socially isolate those that hurt the feelings of others and express behavior that is unsatisfactory (Mill 1859, 73). Society should attempt to resolve these sorts of interest infringing behaviors and attempt to refute the seeming immoral acts of those that injure the feelings of society’s members (Mill 1859, 75). Though, no governmental intervention is justifiable when only the interests of people is infringed, and no harm to rights is committed.

Additionally, to address the assertion that trans* people are not welcome at schools when their preferred pronouns aren’t used, nowhere in Mill’s harm principle is it clear that government intervention is permissible when people do not feel welcome in society. Proponents of compelled speech laws such as seen in Bill C-16 and New York’s Human’s Rights Act argue that the government has the jurisdiction over psychosocial interactions of people and believe that the government should step-in to ensure that these people are welcome and socially assimilated (Wilson-Rebould, 2016; Volokh, 2016). In fact, by Mill’s harm principle, these people, considering they are distant from the normal gender expression should expect to encounter harsh judgement and social ostracization until society begins to accept them. Mill believes rightfully that society should be able to reprobate people and condemn them for their atypical behaviors and expression. This, as many trans* advocates would argue, has been the norm and this tradition of socially acceptable discrimination should come to a stop. I, and Mill would probably agree that this moral reprobation and discrimination should stop because trans* people deserve equal respect, though, there is no right to respect, and the government should never dictate the psychosocial or interpersonal interactions of society’s members when no right-infringing physical, directly financial, or coercive forces are harming the trans* people.

Ultimately, the social atmosphere of pressure, criticism and majority opinion will shift to indoctrinate the youth and adults to accept these trans* people, but none of this should be forced by the ascendant class of policy makers because the policy makers do not represent the omnipresent ideologies of all people. They only represent a slice of the philosophies about sex, gender, and self-identification, which are ever-changing, and to impose these philosophies on the rest of humanity by law is harmful to free-speech, opinion and freedom of expression, which undermines the utility of all people and leads to the tyranny of the ascendant class over the descendent classes.

References

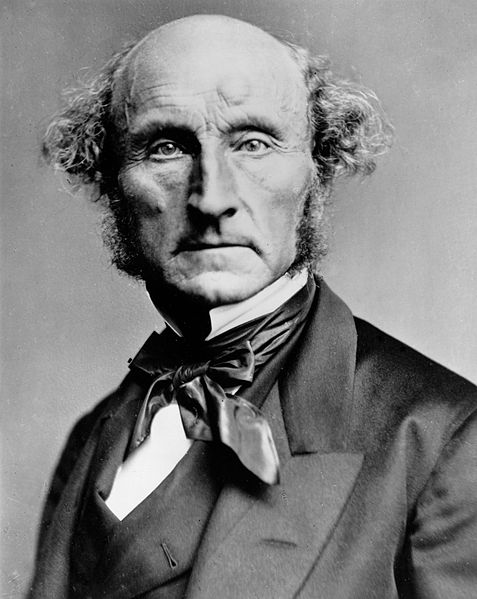

Mill, John Stuart. 1859. “On Liberty.” Chapter 1: “Introductory.” no. 6-18. Chapter 4: “Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual.” no. 69-86.

Lewis, Noah. 2016. “For trans people like me, pronouns are about more than grammatical correctness”. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2016/06/24/for-trans-people-like-me-pronouns-are-about-more-than-grammatical-correctness/

Jody Wilson-Rebould. 2016. “An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code.” Open Parliament.ca. https://openparliament.ca/bills/42-1/C-16/

Eugene Volokh. 2016. “You can be fined for not calling people ‘ze’ or ‘hir,’ if that’s the pronoun they demand that you use.” Washington Post. “https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2016/05/17/you-can-be-fined-for-not-calling-people-ze-or-hir-if-thats-the-pronoun-they-demand-that-you-use/?utm_term=.8e9c8425be4b”